Introduction

The following series of blog posts summarizes PLG (product-led growth) and PLS (product-led sales) motions — what they are, how to initiate them, and what to avoid.

What PLG? Product-led growth is a method that relies on customer acquisition, conversion, retention, and expansion through the experience they have when using your product/service. In short, show, don’t tell/promise. A well-crafted PLG motion produces long-term revenue if done right and in the right context – for a relatively uncomplicated product in the early/mid stages of its lifecycle.

Leah Tharin’s detailed post on when you should focus on PLG (and when you shouldn’t) is a great read. To summarize, PLG can be beneficial for commoditized markets where the product serves a recurring need, can be easily explained to others, and the value can be experienced in a short time. Downmarket SaaS products are usually great candidates. A newly invented product category, however, will struggle to showcase its value to users and spread via word of mouth.

Let’s zoom out and take a step back. Before you start thinking about growth motions such as PLG and PLS, make sure you have product-market fit (PMF). Sean Ellis, author of Hacking Growth, and the first marketer at Dropbox came up with a simple way to check for PMF after comparing results from hundreds of startups. The Sean Ellis Test (or 40% Test) is a qualitative survey that looks at the percentage of users who would be “very disappointed” if you took the product away. If it’s above 40%, congrats! You have PMF. If your product doesn’t have a PMF or struggles to retain free users that eventually monetize, then do not scale with any growth motion. Instead, focus on defining your core product value and allowing your early adopters to experience it with as little friction. During the initial stages of a product launch, focus on learning about your users as much as possible. Free users make for excellent product analytics. Understanding what makes any user convert is a great indicator of what Marketing should double down on. The flow below can serve as a guide for going from pre-PMF to growing and scaling your product.

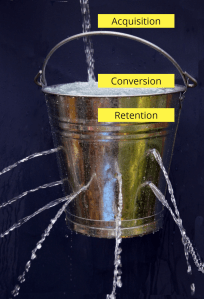

The Leaky Bucket analogy

In a recent webinar, Dan Olsen elegantly uses the leaky bucket analogy to explain why newly launched products should first optimize retention, then conversion, and finally acquisition.

In the image above, the force of water flow from the tap represents acquisition. The stronger the force of flow, the higher your customer acquisition. However, if you’ve got a leaky bucket, no matter how quickly you acquire customers, poor retention (% of active users over time) will inhibit growth. Acquisition metrics can sometimes mask issues with retention – look at each metric in isolation. Look at the following chat – which product would you rather own? Product A or Product B?

At first glance, both products look the same when you look at just the active users, right? However, when you segment those active users into new and returning users, you will notice the difference between the two products:

While Product A has a higher acquisition rate, Product B has a much higher retention. Which product is more likely to have higher long-term growth? If you said Product B, that is more likely to be true.

In the leaky bucket analogy, conversion is depicted as the amount of water that stays in the bucket. Once again, low retention will hinder long-term conversion – the percentage of prospective customers getting into and staying in the bucket. Therefore, for newly launched products, you want to focus on the following order:

- Optimize retention – fix the leaky bucket

- Optimize conversion – optimize the amount of water staying in the bucket

- Optimize acquisition – increase the force of the water coming out of the tap and into the bucket

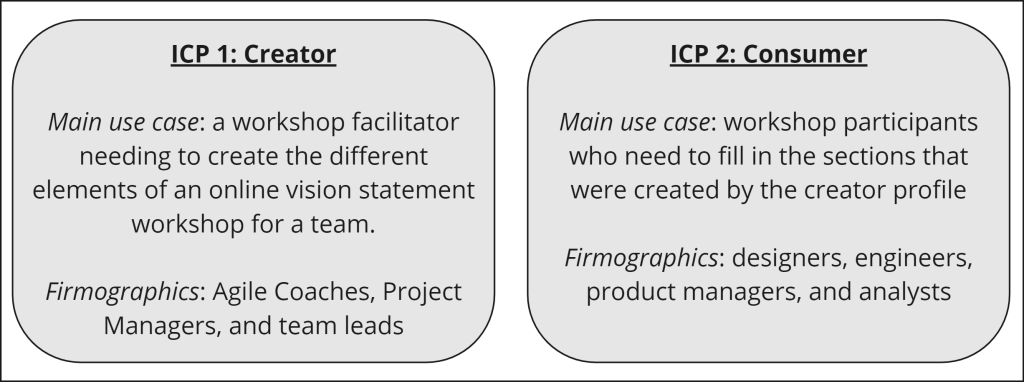

ICP definition

Ideal customer profiles (ICPs) are user types that should be your beachhead segment, a section of the target market that you have purposefully selected to conquer first. Defining ICPs is the first step in kicking off a PLG/PLS motion. ICPs are use case hats that different roles wear. Let’s take the example of Miro, an online whiteboarding tool. Two potential ICPs for Miro could be creator and consumer.

A creator’s main use case could be a workshop facilitator needing to create the different elements of an online vision statement workshop for a team. These elements could include an icebreaker, reviewing the company vision, a video for people to watch, a brainstorming section, and so on. The firmographics for this creator ICP could include Agile Coaches, Project Managers, and Team Leads. These are the roles in a company that may have the use case related to this ICP.

A consumer’s main use case could be that they need to fill in the sections that were created by the creator profile. In the example of the team workshop, the roles that can wear this ICP hat would be all the workshop participants. The firmographics would include designers, engineers, product managers, and analysts.

Rather than focusing on the roles that make up the firmographics, tracking ICP behavior/use cases makes more sense when considering that different roles may act as multiple ICPs, often simultaneously. Consider a team lead who facilitates the team workshop (creator ICP) and also participates in the brainstorming section with the rest of the team (consumer ICP). Both Lenny Rachitsky and Maja Voje have detailed steps for defining your ICPs. Keep this part simple—most products won’t need more than 2-3 ICPs defined.

Identify these profiles through qualitative data (ie interviewing potential customers) first – look for use cases that show interest in your product’s core value, have a burning pain point, show a willingness to pay, show healthy growth potential for other (sub) products, and users who you can easily access. Then validate the ICPs through quantitative data (ie solution testing a prototype with alpha users, MVP analytics, high retention, quick-to-reach success moments, etc). Looking at quantitative data before qualitative data can lead to confirmation bias, where you only talk to users who engage with your product. Quantitative data doesn’t tell you why an action was performed – why they engaged in the first place. You might be missing potential ICPs who didn’t engage with your product because the onboarding was too difficult to find/follow through.

In summary, define your ICPs with the following steps:

- Start with qualitative data first rather than existing quantitative data. Talk to customers to narrow down their problem-solution fit.

- Define what the user does rather than who they are (behavior, use case mapping). Firmographics are secondary. Look for common patterns in the use cases.

- Narrow down and segment your 1-3 ICPs as much as possible to the smallest group that signals high retention in your product.

Once you’ve defined your ICPs, review measures such as frequency of use, technical proficiency (do they often need handholding to go through your product? how many times are they reaching out to customer support/sales? what functionalities are they using/struggling with?), and competition (what other products are they using for their problem? how are they using it?). In addition to focusing only on your ICPs, you want to stop adjacent (non-ICP) customer acquisition and reduce their support cost. Spending time and money on these profiles limits how well you can serve your main customers, your ICPs.

Effectively defining and targeting your ICPs gives your organization a strong sense of focus and optimizes your product distribution for speed and efficiency. Your subsequent interactions with the ICPs can feed into and improve your core product value’s success moments to retain and monetize as effectively and quickly as possible. The next blog post will look at this in more depth.

3 thoughts on “PLG Introduction and ICPs”